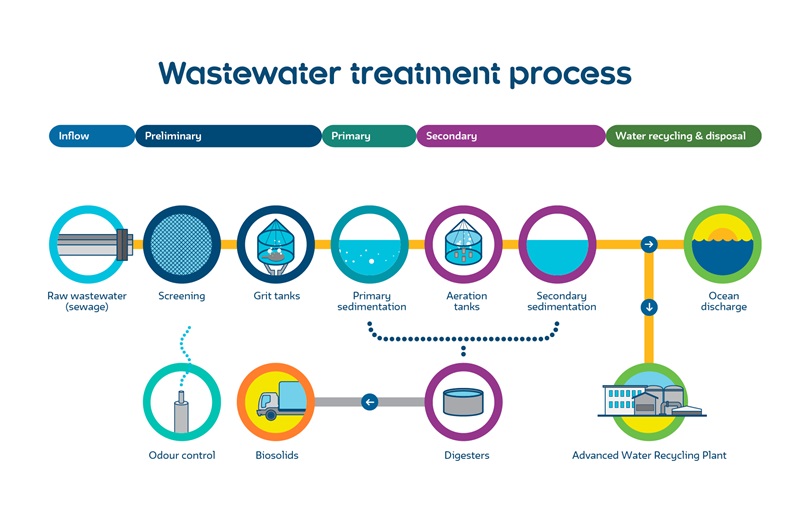

How wastewater is treated

An important part of our role is to make sure wastewater is safe enough to reuse or return to the environment.

Every day we supply over 2 million people with clean drinking water. We also remove around 450 million litres of wastewater per day from water used in showers, sinks, toilets, dishwashers and more. That’s the equivalent of 180 Olympic size swimming pools!

Although wastewater is 99.9% water, we still need to remove any dangerous pollutants before we can release it back into the environment.

Wastewater is pumped or carried by gravity along our sewer mains through to our wastewater treatment plants. Once it reaches the treatment plant, we begin our rigorous treatment processes.

In this article we explain how we treat wastewater and where the water goes once it's treated.

Stage 1: Preliminary treatment

Once the wastewater reaches the plant, we remove large objects like rags, plastic and rubbish using specially designed filter screens.

We’ve seen many unusual things arrive at our wastewater treatment plants, from cotton buds, baby wipes and false teeth to Barbie dolls. These objects can clog up our machines and damage equipment. That's why it's important to only flush the three Ps: pee, poo and (toilet) paper.

After screening, the wastewater goes through our grit removal tanks. Heavy inorganic materials like rocks and minerals sink to the bottom of the tank. When the water settles, we drain the tank and the water flows onto the next stage of treatment.

We dispose of any rubbish and sediment collected at approved landfill sites.

Stage 2: Primary treatment

Next up are the sedimentation tanks (also known as settling tanks or clarifiers). Particles in the water gradually sink to the bottom of the tank and form sludge. Mechanical scrapers push the sludge to the end of the tank, where it’s then pumped to a sludge treatment area.

What happens to the sludge? More on that later…

Stage 3: Secondary treatment

At this point the wastewater looks relatively clear. But there are still bits of organic matter and dissolved nutrients that need to be removed.

To do this, the wastewater goes through an aeration process. We pump air into the tanks holding wastewater to stimulate the growth of naturally occurring microbes. These microbes need oxygen to help them break down organic material.

The microbes form ‘activated sludge’ flocks and feed on the organic matter remaining in the wastewater. The microbes remove contaminants and convert organic matter into carbon dioxide, nitrogen gas and more activated sludge.

The aeration process is a natural alternative to chemical processing. If we relied on chemicals to treat wastewater, we'd also need a process to remove them before returning the water back to the environment.

When the activated sludge flocks have done their job, the water flows through to secondary sedimentation tanks. This is the final stage of the wastewater treatment. We don't need to cover these tanks because by this stage, the water is clear and doesn’t smell.

Stage 4: Water recycling and disposal

Most of our treated wastewater is returned to the ocean via a large pipe. The end of the pipe contains small holes to ensure the wastewater is evenly dispersed into the sea. This is the most cost effective option as the process uses very little energy, instead relying on gravity to transport the water.

Sunlight, oxygen and ocean currents combine to continue the wastewater treatment process. We monitor and test the seawater near our treatment plants to ensure our wastewater is not causing harm.

We also recycle some of the treated wastewater. Wastewater that goes onto our advanced water recycling plants is treated further and used in the following ways:

• irrigation of sports grounds, golf courses and other open public spaces

• irrigation of non-food crops like trees, woodlots, turf and flowers

• replenishment of our groundwater supplies by pumping treated wastewater (after a tertiary advance treatment) back underground

Where does the sludge go?

The sludge collected in the sedimentation tanks is pumped into huge tanks called ‘digesters’. These tanks are 8 meters high and go down another 8 meters into the ground. Each tank holds around 4 million litres of sludge.

We heat the tanks to encourage the growth of bacteria. The bacteria, in turn, breaks down the sludge into water and biosolids—this process is called anaerobic digestion.

The biosolids are trucked off site to be made into fertilizer or used for agriculture.

Methane gas is a primary by-product of the anaerobic digestion process. We recycle some of this gas as fuel for heating and mixing inside the digesters or to produce electricity.

Inside a wastewater treatment plant

Read a transcript of this video